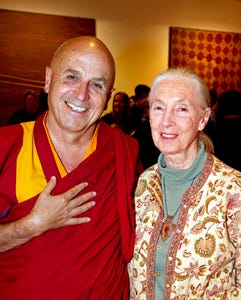

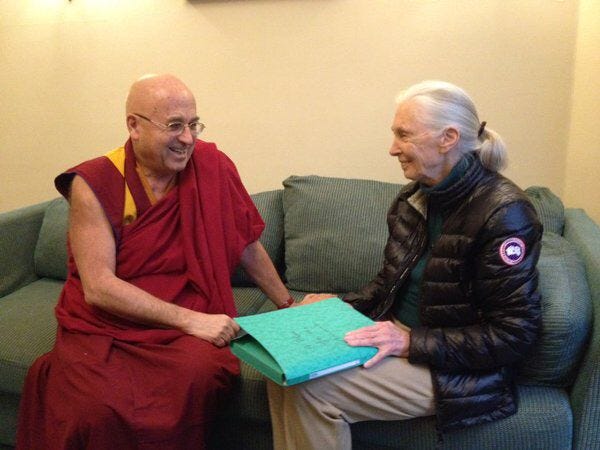

In honor of Jane Goodall’s birthday this week, we are releasing a never-before published dialogue between Matthieu Ricard, author of the recent book, A Plea for the Animals, and the renowned primatologist, animal rights activist, founder of Roots and Shoots and UN Ambassador of Peace. They have been friends for many years, and both lifelong vegans, are tireless advocates of compassion for animals.

Part1 How Animals are Treated.

Matthieu: There is an unbroken connection and continuity between the various animal species and humans. The reality of this continuum should make humans re-examine the way we treat other animals.

Jane Goodall: There is of course no question that there is a continuity of feelings and emotions. There is no question that animals feel pain. I don’t know how far down the scale of species it goes, but I am sure that insects feel some kind of pain since they avoid bad stimulus. In the case of animals with more complex brains it is not only the pain they experience, but also the fear and the suffering, mental suffering as well as physical.

What I find so extraordinary is that people seems to be almost schizophrenic when you speak to them about the terrible conditions in the intensive animal “farms,” this cruel cramming of sentient beings into tiny spaces — so bad that to keep them alive you have to give them antibiotics all the time otherwise they just give up. I tell people about the transportation nightmare, about the abattoirs where so many animals aren’t even stunned before they are skinned alive, plunged into boiling water. It is horrible. If they fall while being transported, they are pulled up by one leg that gets broken. It is obviously excruciatingly painful. When I tell this to some people, they often reply, “Oh please don’t tell me, I am very sensitive, I love animals.” And I think, “What’s gone wrong in that brain!”

The practices of the food industry, the meat eating industry, is particularly shocking because they are condoned by governments and by the people. Even if they do not consciously condone it, they are doing so by eating meat. And these practices are increasing as more and more people want to eat more and more meat. It is destroying the environment, it’s shrinking water supplies, and it’s wasting huge amounts of energy, transforming vegetable protein into animal protein in totally wasteful ways (it takes 10g of proteins from plants to make 1g of meat protein). That’s all quite separate from the huge suffering, the massive, massive, the endless suffering going on everyday. It’s suffering from birth to death.

I grew up eating bits of meat, because we all ate meat, we didn’t even think about where it came from and so on. I only learned about “intensive farming,” or the cruel way that animals are bred and slaughtered when I first came back from Gombé, because it started in England before I left. I looked at this piece of meat on my plate, and I thought: “That symbolizes fear, pain, death.” That was the last bit of meat that I ever looked at on a plate of mine. I haven’t touched meat or fish since.

But in addition to that, there is the animal testing that is going on. It’s pharmaceutical, which is the worst, and then it’s medical. They are supposed to be guidelines, rules and regulations, but they are most of the time not enforced. Here again, you get this schizophrenia: a man has a home, wife and children, and a dog. He talks about his dog as a member of the family, he says, “she understands everything I say”. Then he goes into a lab, puts on a white coat and does unspeakable things to dogs.

In veterinarian schools in America, not in England, they differentiate between the animals they treat. One group has owners, who can pay for the treatments. The others are the animals that are being used for experiments. They have an X on their door. And they don’t get proper anesthetics or anything like that. I know a wonderful philosopher who uncovered all this, Bernard Rollin. He could not understand why young people who went to vet schools, who were really passionate about the animals, loved animals, and wanted to help them, six years later came out cold and indifferent. Gradually their empathy had been killed.

Part 2 Becoming Aware of the Suffering behind Eating Meat

Matthieu: It seems also that slaughterhouses are guarded as if they were top-secret military facilities. You can’t see anything. But if it were shown even a little bit to people, they would find it intolerable.

Jane: There is a wonderful woman in America. She got a job in an abattoir and managed to secretly film what was going on. But the television channels would not show it.

Matthieu: TV broadcasts incredibly gory horror movies, but if you want to show a little bit of what is going on these industrial farms and slaughterhouse, nobody wants to look at it. I guess because it points at our complicity. It is a permanent torture house that goes on and on. How could we revive human values and make people more sensitive to the suffering we create?

Jane: This is what we are doing with “Roots and Shoots”, a program I am doing to engage and empower youth with service. We don’t tell the young people what to do. They sit around, talk, and choose three projects: to help people, to help the environment, and to help the other animals, including domestic ones. I bring these topics into all my talks, and they start thinking and learning, and begin to be completely horrified by what they are finding out. So, they will not tolerate those conditions when they grow up. The only way to sensitize people in the long run is working with the youth. I also meet with senators and congressmen. You have to get to their hearts. They are doing it all through their heads.

Matthieu: If we could show images about what is going on like the documentary Earthlings, people would become aware.

Jane: I had an idea about that. If you do get a film on TV that shows the horror of what is happening, people turn it off. They don’t want to look. They say: “I love animals, I can’t look at that.” They turn it off. Now, I am thinking of children. You could make a film with a very attractive child who is shown with a chicken, or a hen that has been rescued from a battery farm. She has had her beak cut. So you first see a very sweet scene of the hen in the grass with a gentle child. And the child asks: “Why is her beak like that.” Then you have a flash back. You show it being cut in the poultry battery, and quickly come back to the peaceful scene, so that it is not too much. There has to be a story. Then they ask something else and you flashback to when the hen lost all her feathers because she was in this ghastly little space. I have not found anyone to do it, but I will. You could it with animation, but people would not believe that this is true.

Matthieu: You may remember that after the movie Babe that is about a cute, smart young pig came out many children who saw it did not want to eat meat anymore.

Jane: And then it faded away.

Matthieu: Many children actually don’t want to eat meat, but their parents force them to, telling them that they need it for their health.

Jane: My sister’s grandson, when he was five, learned where a chicken came from and said: “I am not going to it that again.” That was the last one. Then he went to an aquarium and went round and round and declared “I am not going to eat a pretty fish again.” Then his mother took him to another part of the aquarium where there was less colorful fish. He watched them for a very long time and finally said, “You know, I am not going to eat any fish.” And he is only seven!

Matthieu: It reminds me of Kafka who, after having given up eating animals, said, while watching a fish in an aquarium, “Now I can look at you in peace, I don’t eat you anymore.”

Part 3 The Endless Killing of Animals

Matthieu: Human intelligence can produce Gandhi and can also produce Hitler. But a superior intelligence does not give humans the right to slaughter at will billions and billions of animals every year. It seems that the value of an animal is practically zero compared to that of a human. During the episode of the Hoof and Mouth Disease, for instance, millions of cows were slaughtered to protect a few human lives at risk.

Jane: That was horrible, and there wasn’t even a need to do so, since you could have vaccinated the cows.

Matthieu: It was done purely on economical, not reasonable or compassionate, reasons. Throughout the world 150 billion terrestrial animals and 1.5 trillion sea animals are killed every day in a state of great suffering, for human consumption. This is not genocide because the motivation and the goal are different. Genocide is motivated by hatred and the goal is to exterminate a population. In the case of animals the killing is motivated by greed, ignorance, and very often cruelty, and the goal is to repopulate them again and again to kill them again and again. But the process and the methods are the same. In the case of genocide, human are dehumanized and devalued, sometimes as “vermin”, in the case of animals they are deprived of their sentience and considered as mere objects, food products, sausage making machines. As for the methods, the slaughterhouses function in very similar way to extermination camps.

Jane: And you know that, in the case of the Nazis, one of the models they used for designing the camps of mass extermination was the large-scale American slaughterhouses. But it is not only the methods, it is the attitude of people working in the abattoirs, people who work in medical research, who stay in places where animals are tortured. Either they can’t stand it and leave or they become immune to it. They can become brutal. I have seen people in a medical research lab holding a semi-anesthetized monkey and make him move his arms like a puppet, shrieking with laughter, and putting a cigarette in the monkey’s mouth… unbelievable.

There is a book about this that I started to read and felt physically ill and thought that I would not bother with this and then I read a little more. It is an extraordinary book called Etre the Cow. It’s about a bull that is doomed to die and tells his story.

Part 4 The Fascination with Others’ Suffering

Matthieu: What about bullfights? It has just been elevated to the status of “national culture heritage” in France.

Jane: In the case of bullfights, perhaps the bull does not suffer as much as cattle in industrial farming and has a relatively good life until the fight, although it is indeed then a kind of torture. But what appalls me is the people who come to watch it. In the old days, people would watch a public hanging; crowds would go and watch the Christians given to the lions… When people go to motor races they crowd around places where there might be a crash, at horse races they gather where there are dangerous jumps, expecting perhaps to see the horse break his neck. It is obviously some kind of thrill they get that gives them a buzz. Why would we want to look at torture?

Matthieu: To want to watch it for your own enjoyment… isn’t that the opposite of compassion?

Jane: Yes. Of course it is. It is the opposite of compassion and empathy.

Matthieu: You might remember the movie by the French poet Jean Cocteau, Beauty and the Beast. The beast was “ugly” but he had some noble and almost likable features. You could perceive a moving sadness and good-heartedness behind the ugliness, while in the modern remake and other similar movies, the faces of “beasts” express nothing but malice, cruelty and hatred. And it is indeed the case for all “monsters” that are omnipresent in movies nowadays.

Jane: I am counting on the youth and on inspiring them in a different way. They will be the next politicians, lawyers, and scientists.

Matthieu: If the youth deeply value the need to treat animals in a more decent, respectful and compassionate way, they will also make their elders more aware and bring about change.

Jane Goodall in Dialogue with Matthieu Ricard, June 17, 2011 Brisbane, Australia

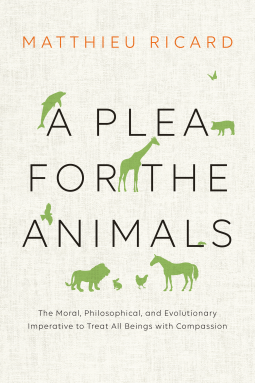

“Are animals mere things, here for us to exploit? Or are they rather sentient, often intelligent beings, entitled to live their own lives? Matthieu Ricard examines theological, philosophical, and scientific thinking on both sides of the issue and concludes that without doubt we must recognize each animal is an individual deserving of our compassion and respect. A Plea for the Animals is fascinating, instructive, and compelling, speaking to us on both an intellectual and emotional level.” — Jane Goodall

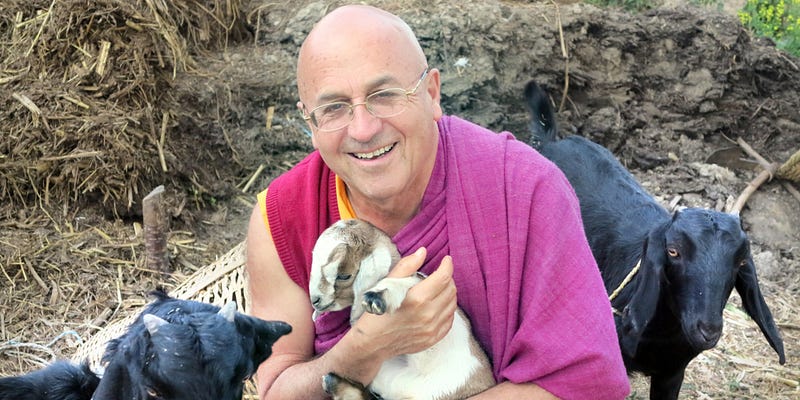

All proceeds from Matthieu Ricard’s books, photographs, and events are donated to Karuna-Shechen, the humanitarian organization he co-founded to assist disadvantaged communities in Nepal, India and Tibet, based on community engagement and empowerment, grassroots cooperation and respect for unique cultural identities. Karuna means “Compassion.”

Comments