Here's what happens when researchers make people visualize their own deaths.

Does thinking about death make you more grateful for life?

This is an especially timely question for us here at the Greater Good Science Center, where we’ve been mourning the loss of Dr. Lee Lipsenthal. Lee was scheduled to speak at our seminar this Saturday, “Taking in the Good,” before he passed away last month from esophageal cancer.

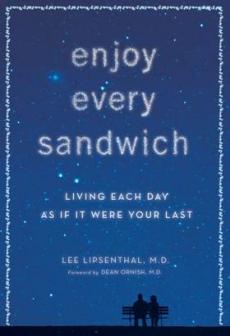

In the time leading up to his death, Lee inspired those who knew him with his perspective on both his illness and on the limited time he knew he had left on the planet—a perspective captured in his forthcoming book, Enjoy Every Sandwich: Living Each Day as If It Were Your Last, which is all about savoring life as we live it. Not coincidentally, that’s the theme of our event this Saturday as well.

Despite—or perhaps because of—his diagnosis, Lee was determined to live not in fear of death but with joy, purpose, and gratitude for life. (Christine Carter reflects on Lee and his effect on her own life in her post yesterday.)

So it was with Lee on my mind that I dug into a fascinating recent study in the Journal of Positive Psychology that substantiates the link between gratitude and death.

In the study, researchers from Eastern Washington University and Hofstra University wanted to explore how to boost people’s levels of gratitude, since prior research has found that gratitude can have lasting effects on our health and happiness. In particular, they wondered whether people truly become more grateful for what they have in life when they recognize that none of it was inevitable and all of it is temporary—in other words, when they recognize their own mortality.

The researchers measured the levels of gratitude among their study participants, then placed them in one of three groups. Members of one group simply visualized their typical daily routine. Others described (in writing) their thoughts and feelings about death. And the third group actually imagined themselves dying in a real-life scenario in which they found themselves trapped by a fire “on the 20th floor of an old, downtown building,” by the researchers’ description, and made “futile attempts to escape from the room and burning building before finally giving in to the fire and eventually death.”

After going through these mental exercises, the participants again reported their levels of gratitude.

The results show that the people who simply wrote about death in a more abstract way didn’t feel any more grateful afterward; the people who just imagined a day in their life seemed very slightly less grateful.

But the gratitude scores of people who actually visualized their own deaths skyrocketed. These people seemed deeply affected by confronting their own mortality “in a vivid and specific way.”

The researchers note that their findings resonate with stories of people who have near-death experiences or life threatening diseases—they report more gratitude for life. This study shows that this gratitude is real, and dramatic.

“Because our very existence is a constant benefit that we adapt to easily, this is a benefit that is easily taken for granted,” write the researchers. “Reflecting on one’s own death might help individuals take stock of this benefit and consequently increase their appreciation for life.”

Of course, there are some obvious limitations to this study and its relevance to everyday life. For one thing, it measured just short-term gains in gratitude from a very dramatic exercise; we can’t really expect people to visualize their own deaths over and over, it would be too draining (and possibly traumatizing).

It seems like the challenge presented by this study is how to heighten our appreciation for life without constantly obsessing over our own deaths, not to mention actually suffering from a life-threatening illness.

At the very least, this study—like Lee’s life and legacy—offers a powerful reminder of the importance of regularly counting our blessings. In fact, prior research has found that just thinking about the absence of a positive event in our lives or the loss of a spouse heightens people’s appreciation for those things.

In other words, write the researchers, “being confronted with the possibility that any benefit ‘might not be’—including the benefit of life itself—might increase one’s gratitude and appreciation for those benefits.”

So how to get started living a more grateful life? One of the simplest—and most research-tested—ways is to keep a gratitude journal, in which you regularly record the things for which you’re most grateful.

https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/the_grateful_dead

About the Author

Comments